How does Frank Zappa compare to Jimmy Page, Jimi Hendrix, and Eric Clapton?

These are four musicians that I’ve admired and enjoyed in varying degrees over the years. If we’re going to compare them with each other, I think we have to look at all of them as being more than just guitar players, because that’s not the only thing that they’ve all done.

This answer may well come across as a tad pretentious, but I’m looking at it from the perspective of someone who’s interested in a lot of different music, not just blues-based guitar playing. So that’s my standpoint: to try and see these four guys in the round, so to speak, and perhaps to see if they can be compared with each other, without making empty and foolish claims about one being objectively better, etc.

If some component of my personal opinion comes into this it’ll hopefully be obvious, and it should go without saying that I mean it as opinion.

Whether it convinces the reader or not is a matter of how well I explain myself.

You might want to get a beverage, at this point. This will be a long one. And I make no apologies.

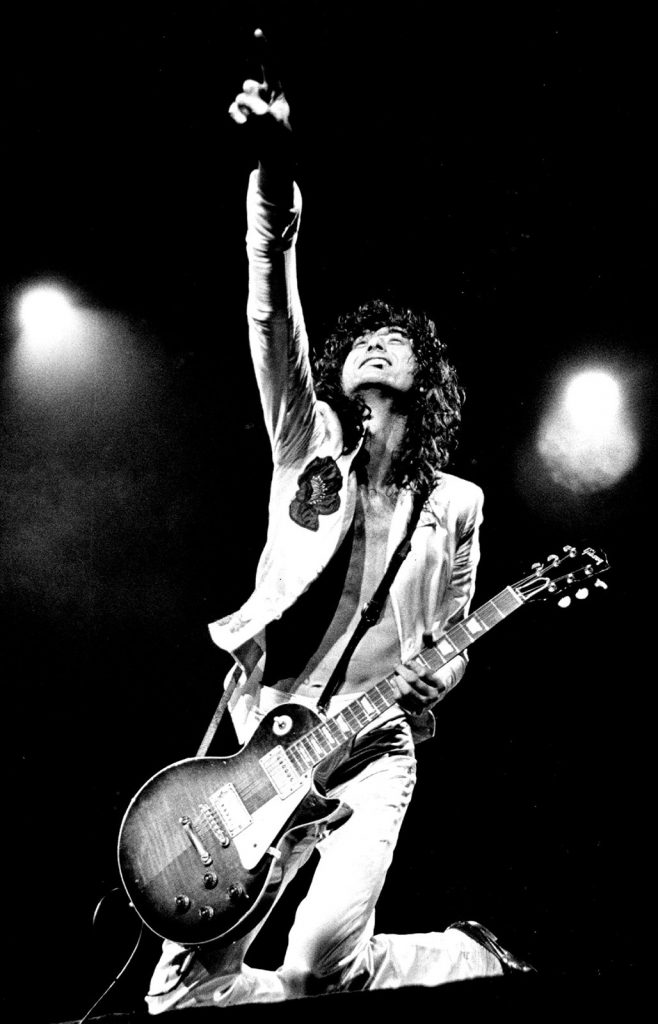

Jimmy Page

immy Page combined various types of musician into one.

He’s a remarkable guitarist, obviously. A genuine stylist. And also a notable songwriter.

In general, I prefer his rhythm playing to his lead playing, because he’s one of the brilliant riff-makers of any period in rock music, which is a highly underrated talent.

Guitar fans routinely overvalue flashy technique at the expense of the ability to make memorable and effective music that communicates with people. Page has some chops, for sure, but many of his most striking creations (‘Whole Lotta Love’, ‘Immigrant Song’, ‘Good Times Bad Times’, ‘Communication Breakdown’) are well within the reach of the average bedroom guitarist.

This, perhaps, is why that aspect of his talent is so underrated: since so many bedroom guitarists find him relatively easy to play, they fail to realise that the ability to come up with riffs like that at all, is a gift that they themselves lack.

But there’s another thing about him, which is the reason why, rather than have a picture of him onstage, I wanted a picture of him in the studio.

Page’s riff-making is part of his larger gift of musical construction.

He had a sound in mind for Led Zeppelin, and he chose the musicians that he wanted to help him create it.

From the very first album, there’s a blocky clarity about Zeppelin’s music, that you don’t find in the Yardbirds, and you don’t find in Zeppelin’s peers, except perhaps Black Sabbath, a bit later on.

You can almost see Led Zeppelin’s guitar and bass and drum parts, as they lock together, and you can almost wander through the space between them. That is, when they weren’t doing full-on balls-to-the-wall rock and roll, like in ‘Rock and Roll’ or ‘Celebration Day’ or ‘Achilles’ Last Stand’. Page is a producer as well as a musician, and his production fingerprint with Zeppelin is a big feature of why their recordings have continued to sound so good. He knew what he wanted, and he got it.

Only later, when stupefying success and overindulgence caused him to lose focus, do Zeppelin’s albums start sounding…not exactly like they could be anyone’s, but like the rock beast has been fatally wounded, and is stumbling blindly on, waiting for Legolas to climb up its legs and give it the coup de grace.

I was too young ever to see Zeppelin live, but live recordings and video of them don’t have nearly the appeal for me as their studio recordings do. That’s why I think of Page as being at his happiest and best in the studio, carving those epic recordings out of silence with his three bandmates. (Of course, we know that John Bonham was also happiest when he wasn’t touring, so there’s that.) And that’s why I chose a picture of him in the studio, looking happy.

So, as a creator of a sound, for a very specific purpose—not an inarticulate, bullying visionary like Captain Beefheart, but as a calm and focused bandleader who knew what he wanted—that’s what I value most about Jimmy Page.

He was the principal architect of some damn good tracks.

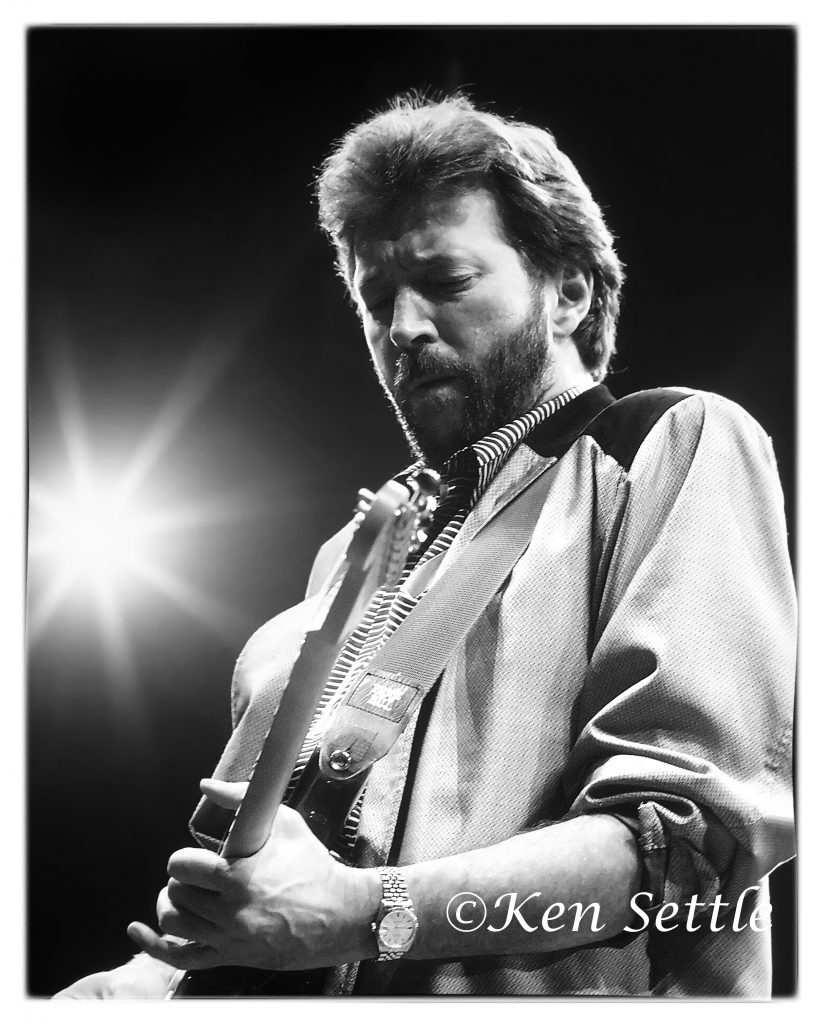

Eric Clapton

Eric Clapton is a bit different.

The reader may start to notice that I have not made my image choices lightly.

I’ve already gone into my whole Clapton thing elsewhere, but brief recap:

When I first wanted to learn guitar, I knew little about it, so I asked around for who the best guitarist was. The only answer I got was ‘Eric Clapton’, so I dutifully listened to a shitload of Clapton, and it took me a long time to realise that I found most of it very, very boring. The only period of his career that I found consistently rewarding was the first five years, in which he was in no less than five bands: the Yardbirds, John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, Cream, Blind Faith and Derek and the Dominoes.

Clapton is not a visionary musical architect, like Jimmy Page.

He began as a singing guitarist, and that’s still basically what he is. More than any other guitar player of his generation, he’s invested the most time in playing the role of the solitary virtuoso.

One man, with a guitar, singing the blues, in a very expensive suit.

He has never been his own producer, except kind of on Layla and other Assorted Love Songs, where Tom Dowd was the executive producer and the whole band got production credit. The overall sound of Clapton’s music over the years has been shaped largely not by him, but by the company he keeps, and (at least in the seventies and eighties) by whatever was the state of his hangover that day.

The virtuoso tradition grew in the nineteenth century, and because of its focus on the skill and heroism of the virtuoso, it’s always tended to shove the accompaniment of the virtuoso’s performance into the background. For all that Clapton has hired some great sidemen, does anyone listen to his recordings just for them? Has he really brought out what’s great about them? On some of his 70s recordings, the heavy lifting in terms of guitar playing isn’t even by him, but is by George Terry, his second guitarist, because Clapton was too drunk to deliver.

Fine: he got his act together, and since the 90s, he has been sober, conscientious and disciplined. And as his post-alcohol nerves have steadied, he has all the more conscientiously attached himself to the virtuoso tradition, as it was established in the 19th century, although in his case it’s in a comfortable blues-country-rock mode, not exactly the challenging conditions of a classical work. (Chopin used to show off, by playing his own concerti as solo works. Has Clapton ever made an entirely solo recording?)

But since Clapton got himself together, has the music been as effective?

What I’m arguing is that Clapton’s greatest focus, and I think most of his value for his fans and admirers, goes into a very narrow field: his guitar playing. And if you’ve got an appetite for it, and it does the job for you, then he certainly delivers something.

I’m less convinced by the whole solo-bluesman thing. Because I think that there are aspects of the blues that almost entirely escape Clapton.

I’m going to quote a distinguished African-American authority on the music, Albert Murray, who had this to say in Stomping the Blues, which was described by Greil Marcus as ‘the best word [on the blues] anyone has offered for a long time’:

That the blues as such are a sore affliction that can lead to total collapse goes without saying. But blues music regardless of its lyrics almost always induces dance movement that is the direct opposite of resignation, retreat or defeat. Moreover, as anyone who has ever shared the fun of any blues-oriented social function should never need to be reminded, the more lowdown, dirty, and mean the music, the more instantaneously and pervasively sensual the dance gestures it engenders.

This earthy, celebratory aspect of the blues is something that you can hear on a classic blues album like B.B. King’s Live at the Regal, but it’s not something that I would associate much with Clapton.

At the risk of annoying my friend Mr. Tom Robinson, whose learned love of both blues and Victorian poetry surely exceed my own:

Clapton is the Tennyson of the blues.

He has a compulsion to weep and moan, rather than take Albert Murray’s advice:

The main thing, whatever the form, is resistance if not hostility. Because the whole point is not to give in and let them get you down.

This is perhaps why those of us who no longer love Clapton, no longer love him. The blues can haunt us all; but we have to exercise our sympathies a good deal harder, in order to see them dancing around the soul of a maudlin, Armani-suit-wearing, Tory-voting millionaire.

For all Clapton’s dexterity and sincerity, what he chooses to say in his music just isn’t that pressing, and hasn’t been for a long time.

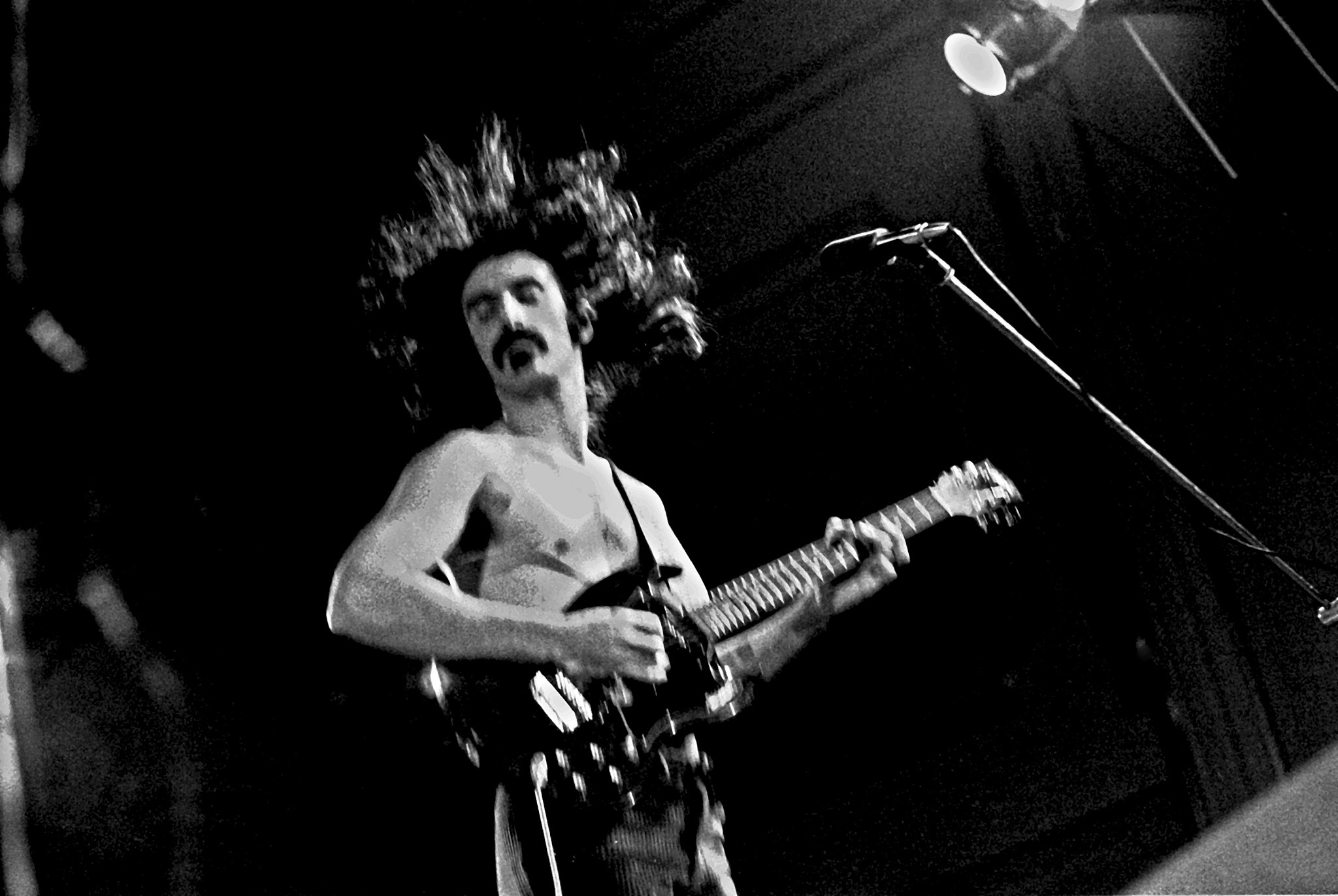

Jimi Hendrix

Jimi Hendrix didn’t live long enough.

He got his most fitting epitaph from Jesus himself, in Mark 6:4:

καὶ ἔλεγεν αὐτοῖς ὁ Ἰησοῦς ὅτι Οὐκ ἔστιν προφήτης ἄτιμος εἰ μὴ ἐν τῇ πατρίδι αὐτοῦ καὶ ἐν τοῖς συγγενεῦσιν αὐτοῦ καὶ ἐν τῇ οἰκίᾳ αὐτοῦ.

And Jesus said to them, “A prophet is not without honor, except in his own country, and among his own kin, and in his own house.”

It still baffles and offends me that there are rock guitar fans out there, who are still unwilling to accept the extent to which Jimi Hendrix changed the way we think about the guitar in music.

Hendrix’s peers accepted it.

The Claptons and Townshends and Becks, and even the McCartneys, gladly allowed his influence to flow into their music, and they absorbed and digested it. (Unless, like Robin Trower and Randy California, they didn’t digest it at all, but just played it back as if they’d thought of it themselves.)

And then their fans in turn praised, in the music of those white rock musicians, the very thing that Hendrix had inspired them to do.

Except for those fans who insisted that he didn’t belong to that company, because he was too ‘messy’ or was just playing ‘distorted blues’, or whatever.

This was not a new strain in Hendrix’s reception. Jon Landau’s review for Rolling Stone of Are You Experienced? had hardly been overflowing with praise:

Above all this record is unrelentingly violent, and lyrically, inartistically violent at that.

As Joe Carducci sardonically noted, I believe Jon lowered his stylus onto the rubber mat, here.

Hendrix came from the musical background that his white British peers only knew from listening to the recorded evidence of it.

I already talked about Jimmy Page as having a sound in his head which he wanted to create. Well, Jimi Hendrix was his precursor, in that respect: the first great visionary of rock guitar, the guy who understood that it was capable of being a fundamentally different instrument from what it had been in the hands of Scotty Moore or James Burton or anyone else who’d stuttered his way across a rockabilly record.

In five short years, Hendrix, like Moses, sketched out a promised land, and huge numbers of his followers entered into it and took up possession.

And then, when they were asked, far too many of them said Oh yeah, I was never really a Moses guy, my real influence was always Aaron.

I still marvel at Hendrix’s sheer eloquence on guitar: his capacity to make it convey whatever mood he wanted, whether it was apocalyptic or sensual or angry or Promethean, or wispy, or cheerful, or sad, or even comical—his 1969 Albert Hall performance of Elmore James’ ‘Bleeding Heart’ is both a devastating blues, and also, as Albert Murray would have appreciated, a hugely entertaining and good-humoured defiance of the blues.

He was tugged this way and that, by expectations and politics and his own appetites, and by events, and he died when he had only just shown us what he meant.

He left us a whole approach to the guitar, a bunch of brilliant recordings, and quite a lot of truly great songs, too. Hendrix’s material has entered the repertoire, in a way that Clapton’s songs, and even Page & Plant’s songs, really haven’t.

His death is one of the great tragedies of 20th century music.

Everything about Hendrix’s career, apart from its end, makes me think that he could have gone on to further greatness.

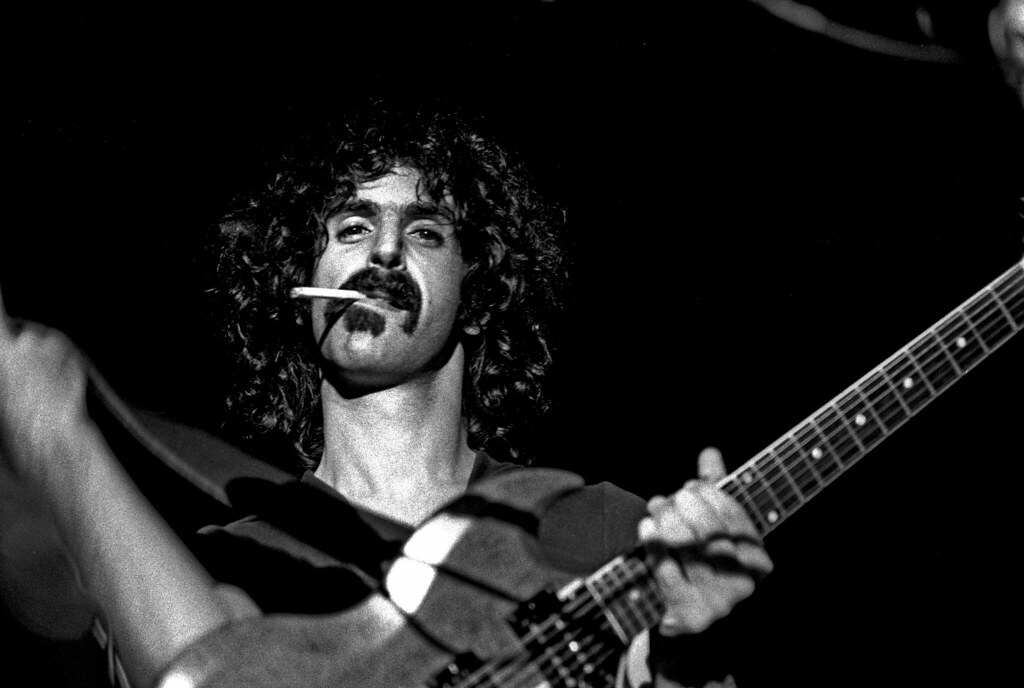

Frank Zappa

And so we come to the oldest and strangest of this quartet: Frank Zappa.

As is probably clear by now, I reckon Hendrix to have been the finest of these four, as a player of his instrument.

Technically he was capable of things that were quite beyond Clapton (in particular, certain kinds of rhythm and chordal playing) and as an innovator, the influence went from him to Page, in terms of how Page went from being a studio guitarist to being a guy who wanted to create a new sound in rock music.

Zappa’s path as a musician was completely unlike the other three. And yet in some ways he resembles all of them.

He began as a drummer in a high school marching band. He liked blues and R&B and doo-wop, became interested in percussion, taught himself to read and write music, discovered 20th century modernist music, taught himself to write it, and then started to take the guitar seriously.

Music for Zappa was firstly a thing that he created as a composer, not something that he primarily wanted to do because he liked expressing himself on the guitar.

As I wrote in another answer, Zappa at the beginning of his recording career wasn’t even a particularly good player. He liked blues, and had definite likes and dislikes in terms of tone and attack, and he became a capable all-purpose lounge/studio guitarist. But the Mothers of Invention had two albums under their belt before Zappa had become a guitar player whose style was instantly recognisable.

No: Zappa was, as he said himself, ‘a composer who happens to be able to operate an instrument called a guitar’. And although he knew Hendrix and played with him in New York in the 60s, and was friendly enough with Clapton to get him to do a spoken-word cameo on We’re Only In It For The Money, Zappa didn’t develop his unique, shiny/filthy, huge sound until the mid-1970s, after years of touring and composing.

And I don’t buy the disclaimers of those who try to argue that Zappa hated rock music, and only played it so he could earn enough money to do other stuff. That sounds to me like the grumbling of those who feel that they’ve been disappointed by his failure to be more sincere, more weepy, more consolatory, when he never tried to be any of those things.

Prolonged exposure to his music reveals the personality behind it: the smart, sarcastic, determinedly unsentimental class joker and local wise guy, who keeps his deepest sentiments buried in his music where nobody can mock him for them, and who rehearsed his expert musicians in hours of seamlessly segued complex music, and then deliberately released live albums in which they (and he) hilariously fuck it up. (But not without recording at least one perfect take, somewhere, because he wasn’t just in it for the money.)

Zappa, like Hendrix, lived a life that could and should have been longer; but with his enormous discography in mind, can we really say that he didn’t get a chance to show us what he could do? I think he proved himself many times, and I think that the people who complain that he was too cynical are themselves the sentimentalists.

Zappa didn’t show a lot of emotion in life, but one of the few times that he did was when he got into a heated discussion with a born-again Christian about music censorship. The born-again Christian (I can’t find out who, sorry), insisted that children were too young to be exposed to things that were ‘not normal sexual relations’. Zappa replied ‘Information doesn’t kill you.’ The born-again Christian insisted that it was better that children remain ignorant of some things. Zappa’s reply was fervent.

Anyone who would rather have their children be ignorant is making a mistake—because then they can be victims.

Because then they can be victims is the secret justification for Zappa’s preference for not making his music a pretext for self-expression, as Clapton did, and not constructing a giant, perfectly articulated rock juggernaut, as Page did.

He wanted the audience to put the pieces together, to figure it out, to see how it all fitted, and not underline everything. He wanted the audience to not sit back and let it all flow over them. He wanted them as engaged as he was.

That, to me, is how Zappa dealt with the legacy of Hendrix’s trippy, visionary output: by making his own junk-sculpture project/object out of blues and doo-wop and rock and ‘Louie Louie’ and Webern and panty jokes, and filth, and secret words, and insane percussion interludes, and epic guitar solos, all of it descriptive of a world where you were in danger at all times of being the victim, because somebody’s got to be, but he wasn’t going to be so arrogant as to pretend that he could lead you out of there.

He just wanted to entertain you, and keep you awake enough to be alert.

In the end, the idea of ranking these musicians against each other is futile.

But for all Clapton’s general solemnity about his art, his music is far less ambitious in scale and intention than Zappa’s, even though Zappa bluffly and rather faux-modestly insisted that it was all just entertainment.

Hendrix was still growing when he died, and we’ll never know what he could have become, but what we have is still the last great conceptual leap forward in rock guitar.

Jimmy Page is a master craftsman, in a time when music had perhaps more than a healthy proportion of inspired amateurs.

In the end, we like what we like, and we are inspired and moved by what inspires and moves us.

All criticism can do is perhaps provoke us into thinking that we didn’t give something a chance—or, alternatively, that we’ve given it enough chances by now.

Reprinted from Quora with permission from the author.